Building a Free and Minimal Unix System (Part 4)- A Minimal Graphical Environment

A graphical environment does not need to be complex to be useful. For many people, the modern desktop has become an all-encompassing system layered on top of the operating system itself: managing workflows, enforcing conventions, and abstracting behaviour behind large, opaque interfaces.

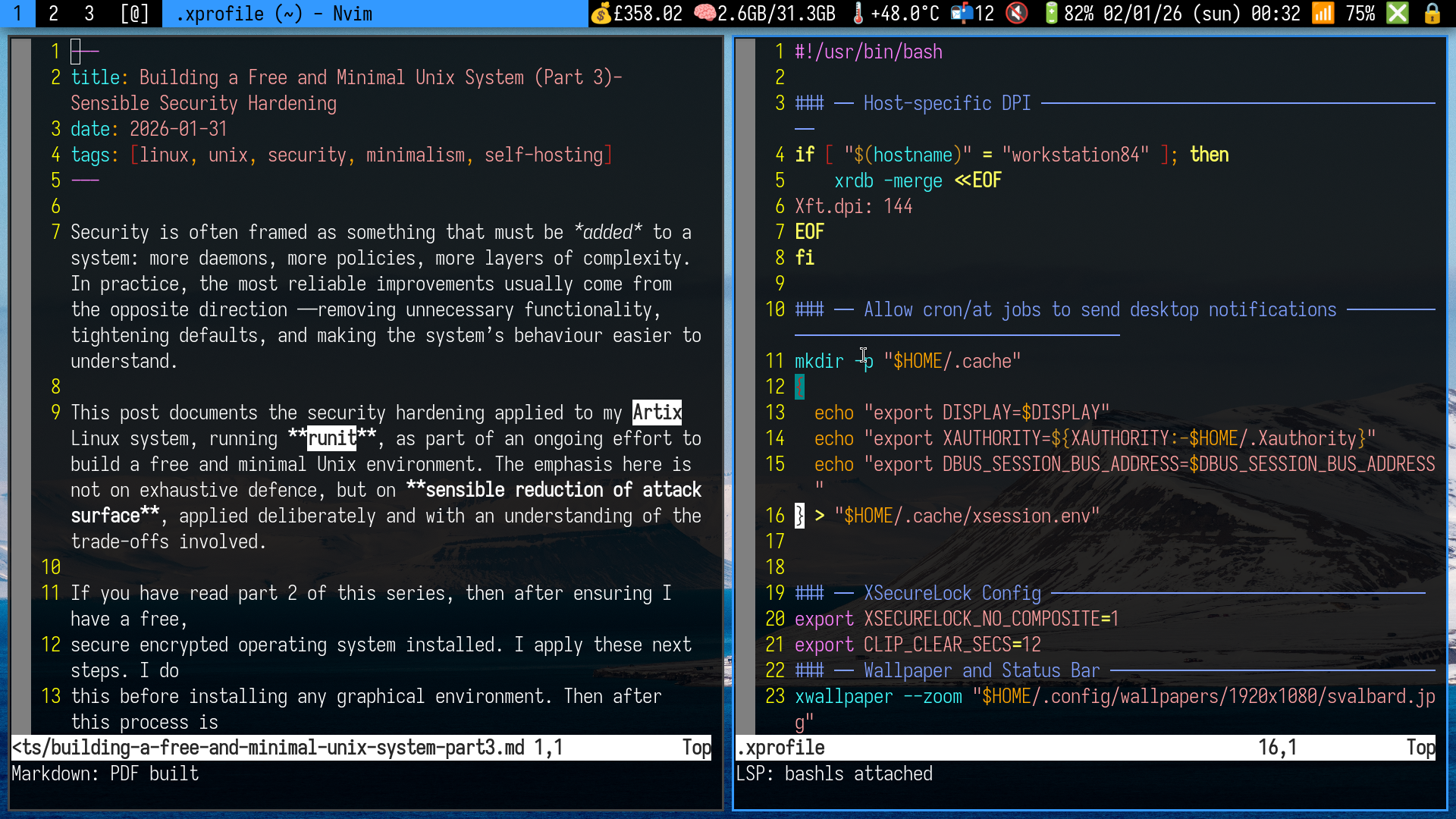

This post describes a minimal graphical environment built on Xorg and a small number of focused tools. It is not intended as a step-by-step guide, nor as something to be copied verbatim. Instead, it outlines a way of thinking about the graphical layer: as something simple, understandable, and subordinate to the work being done.

The goal is not to reject graphical interfaces, but to keep them honest.

A Minimal Desktop, Visually

Minimal dwm-based desktop environment with st, dwmblocks, and text-first tools.

Why a Graphical Environment at All?

Most of my work remains text-based: writing, reading, programming, and communication. The graphical environment exists to support those activities, not to dominate them.

A window system is useful for:

- running multiple programs simultaneously

- displaying documents and media

- providing visual feedback when needed

It does not need to:

- manage workflows

- enforce opinions

- obscure the underlying system

Minimalism here is not aesthetic; it is cognitive. Fewer layers mean fewer assumptions, and fewer assumptions mean fewer surprises.

Xorg as a Foundation

Xorg is unfashionable in some circles, but it remains:

- stable

- well understood

- widely documented

- sufficient for this use case

I use Xorg not because it is perfect, but because it is predictable. It provides a simple mechanism for drawing windows and handling input, and then largely gets out of the way.

This post is not an argument against Wayland. It is simply a description of a system that works, today, without requiring continual adjustment.

The Window Manager: dwm

At the core of this environment is dwm, the dynamic window manager from suckless.org.

dwm has a few defining characteristics:

- tiling by default

- keyboard-driven interaction

- no runtime configuration files

- configuration via source code

This design places effort up front. Configuration happens once, deliberately, by editing C source and recompiling. In return, the system remains stable and predictable over time.

There is no hidden state, no preference panels, and no background services attempting to be helpful. Once configured, dwm rarely needs attention.

For readers new to dwm, Luke Smith’s builds provide a good starting point:

My own setup diverges in places, but his configuration is accessible and well suited to beginners.

Keybindings as an Extension of the Shell

Most of my dwm keybindings do not call window manager functions directly. Instead, they invoke small shell scripts that I have written and refined over time.

This approach has several advantages:

- the logic lives outside the window manager

- scripts can be tested and reused independently

- workflows remain transparent and inspectable

- behaviour evolves gradually rather than being redesigned

The result is a workflow that is deeply personal. Many of these scripts reflect habits and preferences that developed slowly, through daily use, rather than being designed in advance.

This is not something that can — or should — be copied wholesale. The value lies in the process. Readers are encouraged to bind keys to their own scripts and allow their workflow to emerge naturally over time.

With that being said I have to mention here a simple piece of software that I use and abuse in most of my scripts:

- dmenu

Status Information: dwmblocks

Rather than embedding logic directly into the window manager, I use dwmblocks for status information.

This keeps concerns separated:

- dwm manages windows

- dwmblocks runs small scripts

- each script does one thing

Only information that is genuinely useful is displayed: time, battery status, network state. Anything more becomes noise.

Luke Smith’s dwmblocks build is available here:

https://github.com/LukeSmithxyz/dwmblocks

The Terminal: st

The terminal remains the primary interface to the system. For this, I use st, the simple terminal from suckless.

st is:

- fast

- minimal

- predictable

- patchable when necessary

It does not attempt to be a platform. It exists to display text and accept input, and it does that well.

Luke Smith’s st build can be found here:

https://github.com/LukeSmithxyz/st

Most work happens inside the terminal. Improving the terminal experience yields far greater returns than polishing the surrounding environment.

Shells: Interactive Convenience, Scripted Discipline

For interactive use, I use zsh. It provides a comfortable command-line experience with sensible completion and quality-of-life features.

For scripting, however, I deliberately use dash via

/bin/sh.

All shell scripts on this system are written to be POSIX-compliant. This has several advantages:

- faster execution

- simpler semantics

- portability across Unix systems

- fewer surprising behaviours

dash is small, fast, and does exactly what is required of a POSIX shell. Using it forces discipline and keeps scripts understandable long after they were written.

Interactive convenience and scripting correctness are treated as separate concerns.

A Text-First Working Environment

The tools I use reflect a preference for plain text, composability, and transparency.

Editing and writing

- neovim

- pandoc

- latex

Neovim is the primary editor for code, configuration, and prose. Pandoc handles document conversion when required. Work remains text-based until the final moment. Latex is used for most of my academic or professional writing.

Cryptography and secrets

- gnupg

- pass

Secrets are stored as encrypted text files and manipulated using standard Unix tools. This approach is auditable, scriptable, and avoids proprietary abstractions.

- neomutt

Email remains a critical communication tool. neomutt provides a fast, keyboard-driven interface that integrates naturally with the rest of the system, without hiding behaviour behind a graphical client.

File management

- lf

lf provides a lightweight, terminal-based file browser that works well with shell commands and editor workflows. It is fast, simple, and avoids unnecessary visual decoration.

X utilities and screen locking

- slock

- xss-lock

- xclip

- xsel

Small, focused utilities handle clipboard access and screen locking. There is no desktop environment managing policy or state — only simple tools performing specific tasks.

Media

- mpv

mpv is used for audio and video playback. It does one thing well and integrates cleanly with a keyboard-driven workflow.

Build tools

- base-devel

- git

- make

- pkg-config

A minimal system still needs the ability to build software. Treating Linux as a development platform rather than an appliance is essential to long-term control and understanding.

Configuration Effort and Responsibility

This setup took time to understand and refine. That effort is not incidental — it is the point.

Minimal systems shift responsibility from software to the user. In exchange for fewer abstractions and conveniences, you gain clarity and control. When something breaks, the path from symptom to cause is usually short.

This is not a system for those seeking instant comfort. It is for those willing to invest effort once, in order to avoid continual friction later.

Building Your Own

The goal of this post is not to encourage copying my configuration. It is to demonstrate that a graphical environment can be:

- small

- comprehensible

- durable

Readers should take what is useful, discard what is not, and build a system that reflects their own needs and constraints. Minimalism is not a checklist; it is a discipline.

Conclusion

A graphical environment should serve work, not shape it.

By keeping the graphical layer small and understandable, the system remains transparent. Tools behave predictably, workflows remain stable, and attention stays focused on the task at hand.

Minimalism, here, is not about deprivation. It is about choosing tools carefully — and then learning them well.